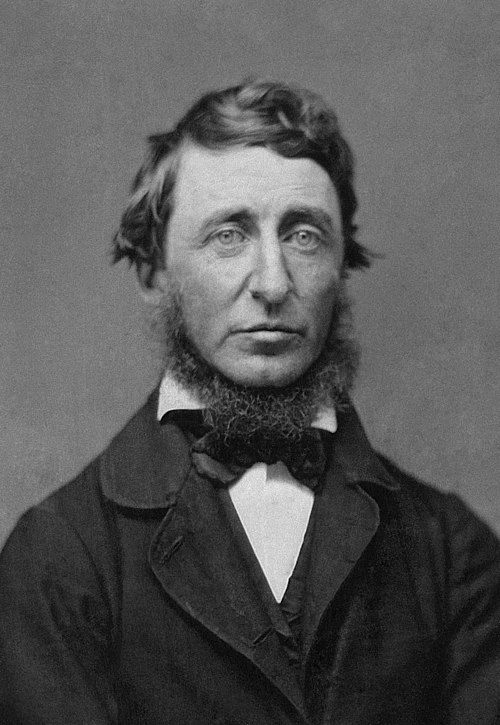

Throughout history, the relationship between the individual and the State has been the subject of deep philosophical reflections. To what extent should a person obey unjust laws? In his short essay, which was originally a lecture given in the mid-19th century, Civil Disobedience, ( Wikisource ) Henry David Thoreau offers a forceful response that goes beyond the common idea that when a government acts tyrannically, it is the moral duty of citizens to resist. He argues that one should not wait for the democratic process to eliminate evil while being complicit in it by financing it through taxes. This text, which serves as an open letter to the American public of the time but could also be addressed to all freedom lovers worldwide, remains a key reference for movements of peaceful resistance.

This small yet significant work reasons the legitimacy and justice of disobeying the government when it becomes tyrannical, as well as the justification for refusing to pay taxes so as not to fund its tyranny. In Thoreau’s context, the main tyrannies were the war against Mexico—a war that was not defensive but one of conquest—and slavery. It is important to note that Thoreau is not arguing about the right to revolution against a tyrannical government in the totalitarian sense, like the government in Orwell’s novel 1984, because he considers that everyone already recognizes that right. He goes deeper; he speaks about injustices committed against others by the government, even when one is not personally suffering from them.

It is not enough, then, to merely express opinions against injustice:

How can a man be satisfied to entertain an opinion merely, and enjoy it? Is there any enjoyment in it, if his opinion is that he is aggrieved?

Here, Thoreau attacks the hypocrisy of those who criticize the government or injustice in theory but do nothing in practice. For him, critical thinking without action is sterile. This connects with the central idea of Civil Disobedience: true ethics do not lie merely in recognizing what is wrong, but in taking an active stance against it. This could be related to Sartre and his concept of bad faith, by which a person avoids or denies their universal responsibility out of fear or conformity. If you truly believe that an injustice exists, why don’t you act? Indignation is not enough; one must resist.

However, Thoreau does not say that every person has the duty to go out and fight against evil, although it would obviously be preferable if those who proclaim their virtue and anger against wrongdoing actually did something rather than just indignantly talk about it. He is not calling for action in that way, but he does establish that it is a duty not to be a direct accomplice in evil. He writes:

It is not a man's duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong; he may still properly have other concerns to engage him; but it is his duty, at least, to wash his hands of it, and, if he gives it no thought longer, not to give it practically his support. If I devote myself to other pursuits and contemplations, I must first see, at least, that I do not pursue them sitting upon another man's shoulders. I must get off him first, that he may pursue his contemplations too. […] The soldier is applauded who refuses to serve in an unjust war by those who do not refuse to sustain the unjust government which makes the war

The metaphor of sitting on another man’s shoulders is especially powerful. It tells us that before dedicating ourselves to our own affairs—whether intellectual, economic, or everyday matters—we must ensure that our comfort is not built on the oppression of others. If I enjoy the benefits of an unjust system without questioning it, I am part of the problem.

The last part of the quote reinforces this idea with a concrete example: a soldier who refuses to participate in an unjust war is admired, but what about those who, without being soldiers, continue to support or finance the government that wages it? This is a critique of the hypocrisy of those who praise resistance yet continue contributing to the system that makes resistance necessary.

Thoreau also demonstrates that he was neither capricious nor an “irrational” combative anarchist, as he did pay the road tax, seeing it as a shared necessity that he himself used. But he establishes that when the machine—a term he repeatedly uses for the government—tries to make you complicit in its injustices, it is your duty to become a resistant friction against its gears.

Parallel to how Bastiat, in those years, stated that when morality and the law contradict each other, one faces the dichotomy of either losing one’s morality or losing respect for the law, Thoreau proclaims that one should not cultivate respect for the law, because the only obligation a person has is to do what they believe is right. The law, he argues, turns those who respect it too much into agents of injustice.

Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail.

On the other hand, this creates a contrast with Socrates, who, in the dialogue Crito, refuses to escape from prison because he believes he owes obedience to the laws of Athens, even if they are being unjust to him. His position thus seems opposed to Thoreau’s, who argues that the law is not a moral absolute. However, both agree on the idea that individual conscience is more important than personal consequences.

Thoreau also recounts how he was briefly imprisoned for refusing to pay taxes—briefly because someone else paid them on his behalf without his request while he was inside—and how he emerged from it strengthened: was this what they thought would intimidate him? The prison cell did not instill fear in him. On the contrary, he saw that for those who have little, doing what is right carries little consequence because they have little for the state to expropriate.

Earlier, I used the word reasons, but Thoreau’s writing employs reason with a strong emotional charge, which is undoubtedly the particular value that has allowed it to endure for 170 years as a reference text against state injustices.

Finally, regarding the necessity of government, we can identify an anarchist spirit:

I heartily accept the motto,—"That government is best which governs least;" and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe,—"That government is best which governs not at all;" and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient.

He is not saying that anarchy is viable at the moment he writes, but that, in an ideal future, when people are virtuous and self-sufficient enough, government will become unnecessary. Here, he suggests that while a state may be necessary, it often acts more as an obstacle than a help. For Thoreau, government is not an end in itself but a means, and if that means becomes unjust or inefficient, it must be resisted or even eliminated.

The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual. Is a democracy, such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State, until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly.

In this quote, Thoreau describes the evolution of political power as a path toward greater respect for the individual. For him, transitioning from an absolute monarchy to a democracy is not the final destination of politics but merely a step toward true freedom. He suggests that society can go even further—toward one that fully recognizes the sovereignty of the individual over themselves. He sees democracy as an improvement but not as the ultimate solution, as it can still impose injustices collectively. For him, the truly free society will be one in which the state does not treat individuals as subjects but as sovereign entities with full self-determination.

These thoughts can be complemented with those of Paul-Émile de Puydt’s Panarchy, Proudhon’s federalist principle, functional, overlapping, and competing jurisdictions, as well as the understanding of freedom and the right of association as also including the right to dissociate from the state through secession—alongside, of course, the idea of a peaceful anarchy.

Translated from Spanish with ChatGPT