Y uno que no es palo ni es monte ni nada.

Con todos los palos que no hacemos monte, deberían hacer carbón para esta temporada de apagones.

Al menos serviríamos para cocinar el sabediosqué que pueda cocinar la gente.

El marabú de nuestras madres es, ante todas las cosas, culpa nuestra.

El carbón que ahora tizna las cocinas de nuestras madre en campos y ciudades, es también culpa nuestra.

El arroz que no existe, el pan que no existe, el libro escolar que se vende por la izquierda, los zapatos llenos de huecos, el robo de los ministros, los balseros, los ahogados, los coyotes... Son culpa de cada uno de nosotros.

No hemos sido ni palos ni montes.

Llenos de hollín en las narices volverán a cantar sus vítores en las plazas. Sea mayo o diciembre.

Cuando me llamó esta mañana, antes de irse a su nueva faena doméstica de traer leña para la casa, con la voz entrecortada me hizo recordar una imagen de mi infancia.

Hay una imagen de mi niñez que se ha hecho muy recurrente. Como si quisiera salir ya hacia mis textos, como si ahora, treinta años después, insistiera en volverse la imagen más importante de mi memoria.

La imagen es un recuerdo hermoso y triste a la vez:

Resulta que, cuando mi hermano y yo teníamos tres o cuatro años, mi madre tenía 19 años. Eran los años más duros del Período Especial. Y ya sabemos que en el campo se pasó peor.

Por la escasez de combustible y de electricidad, había que cocinar con leña. Y mi madre, pese a su corta edad, tenía un par de gemelos de los que ocuparse. Mi madre tenía la crisis doblemente.

Siempre ha sido una mujer que no acostumbra a cruzarse de brazos. Ni a esperar a que alguien resuelva nada para ella. Y menos los hombres. Así que, mientras los hombres de la casa se iba al campo a trabajar, ella nos llevaba monte a dentro, nos sentaba lejos del hacha y empezaba a derribar un campo de marabú para usar la leña en la cocción del almuerzo.

Yo tenía tres o cuatro años y todavía tengo nítida la imagen de la joven lanzando el hacha entre las espinas del marabú para alimentar a sus hijos.

Ha pasado el tiempo. El marabú sigue en el mismo sitio y el hacha no corta como antes.

Pero la fuerza de los brazos de mi madre sigue ahí, siempre presta para alimentar a los suyos.

Ella es mi orgullo, mi gran amor.

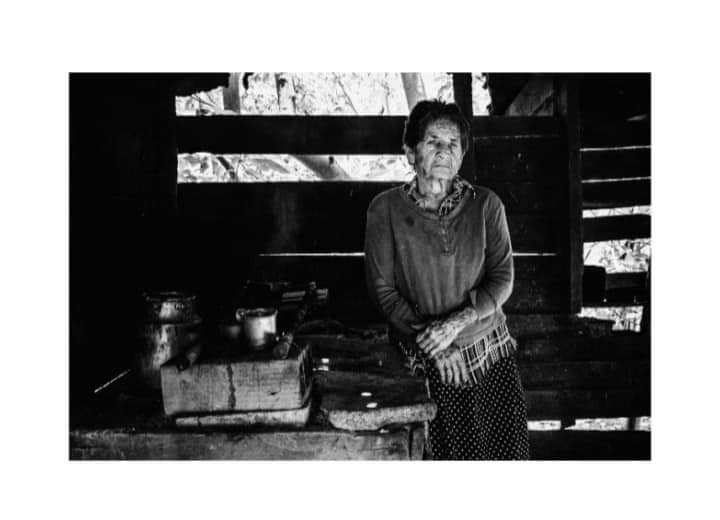

Mientras escribía estas notas , con la imagen aún caliente de mi madre desafiando el monte, evoqué una foto que me regalara un amigo querido antes de emigrar. Es la foto de Bárbaro Walker que presenta este post con el que, además, rindo tributo a todas las madres cubanas que resisten.

El resto de las fotos son de mi propiedad.

ENG

My mother has returned to the wood stove. She has returned to marabou field. No gas, no power.

My mother has returned to what was once a bad experience, a nightmare that no one wants to remember again.

She says that now she is taking my nephew and while cutting the marabou she remembers when my brother and I accompanied her.

And one who is neither a stick nor a mountain or anything.

With all the sticks that we are not, they should make charcoal for this blackout season.

At least we would be able to cook whatever people can cook.

Our mothers' marabou is, above all, our fault.

The coal that now smudges our mothers' kitchens in fields and cities is also our fault.

The rice that does not exist, the bread that does not exist, the school book that is sold on the left, the shoes full of holes, the theft of ministers, the rafters, the drowned, the coyotes... They are each person's fault. of us.

We have been neither sticks nor mountains.

Full of soot in their noses, they will sing their cheers again in the squares. Be it May or December.

When he called me this morning, before going to his new domestic task of bringing firewood for the house, with a broken voice he reminded me of an image from my childhood.

There is an image from my childhood that has become very recurring. As if it wanted to go out to my texts, as if now, thirty years later, it insisted on becoming the most important image in my memory.

The image is a beautiful and sad memory at the same time:

It turns out that when my brother and I were three or four years old, my mother was 19 years old. Those were the hardest years of the Special Period. And we already know that it was worse in the countryside.

Due to the shortage of fuel and electricity, cooking with firewood had to be done. And my mother, despite her young age, had a pair of twins to take care of. My mother had the crisis doubly.

She has always been a woman who does not usually sit back. Nor to wait for someone to solve anything for her. And even less the men. So, while the men of the house went to the field to work, she took us into the forest, sat us away from the axe and began to cut down a field of marabou to use the firewood to cook lunch.

I was three or four years old and I still have a clear image of the young woman throwing the axe between the thorns of the marabou to feed her children.

Time has passed. The marabou is still in the same place and the axe does not cut like before.

But the strength of my mother's arms is still there, always ready to feed her loved ones.

She is my pride, my great love.

While I was writing these notes, with the still warm image of my mother braving the mountains, I recalled a photo that a dear friend gave me before emigrating. It is the photo of Bárbaro Walker that presents this post with which, in addition, I pay tribute to all the Cuban mothers who resist.

The rest of the photos are my property.