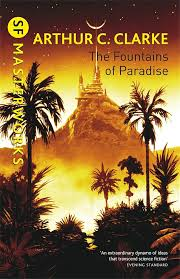

We don't yet have a space elevator. It would be a pretty big engineering process. In 1979, Arthur C Clarke wrote about some strands of carbon filament that would stretch through the sky, beyond the atmosphere, through to orbit, and be a gateway to the stars.

While this book isn't a story about the conquests of humanity after the fact, rather, it is a story of an engineer, inventor, business-man, and visionary, and how on earth (get it?) he would get a tower to rise into the skies, even if that tower was made of impossibly thin and inert material.

This story is one primarily of hope, and of an otherwise not-that well known island near the equator, which just so happens to have beautiful ancient temples upon it.

It makes a striking backdrop of pleasing not only investors, political figureheads, but also an ancient order of pious folk and their history to see the thing get off the ground.

Arthur C Clarke is so good at embellishing wonder into his novels, and his relaxed and simple tones throughout his writing is clearly evident in this book. Reading it is rather effortless, and if you haven't picked up a book in a long time, do so - it is one of the most immersive experiences you can do. (And I say that not as a person who reads a lot in the bathtub).

Wow, this rambling is pretty full of puns.

Having been written in 1979, it is striking to reflect on how much, and simultaneously, how little has changed in the world of science since Fountains of Paradise was released. While our materials science has advanced considerably with developments in carbon nanotubes and graphene, we're still pursuing the same dream of finding a more efficient way to reach space.

For now, rockets are the best we still have. Clarke's prescient understanding of the engineering challenges even speak of orbital junk that has to be blasted out of the sky to make way for the new generation of space-faring tech.

The novel's depiction of computers and telecommunications feels distinctly dated, missing the revolutionary impact of the internet, smartphones, and artificial intelligence. The social and political landscape Clarke envisioned also differs markedly from our reality, particularly in how space exploration has become increasingly commercialised rather than remaining primarily in government hands. Yet his core insights about humanity's drive to push technological boundaries and the tension between tradition and progress remain startlingly relevant.

The book is a relaxing one, and would make a decent film / TV series adaption. How it hasn't been adapted is a wonder to me - it would work really well as a TV series of about two seasons. Yet here we are, in a world where you'll just have to read the book instead.

The conclusion is thrilling, and the epilogue is a wonderful reflection of the aftermath. Who thought a book about engineering carbon and navigating sensitive land rights would be so entertaining?