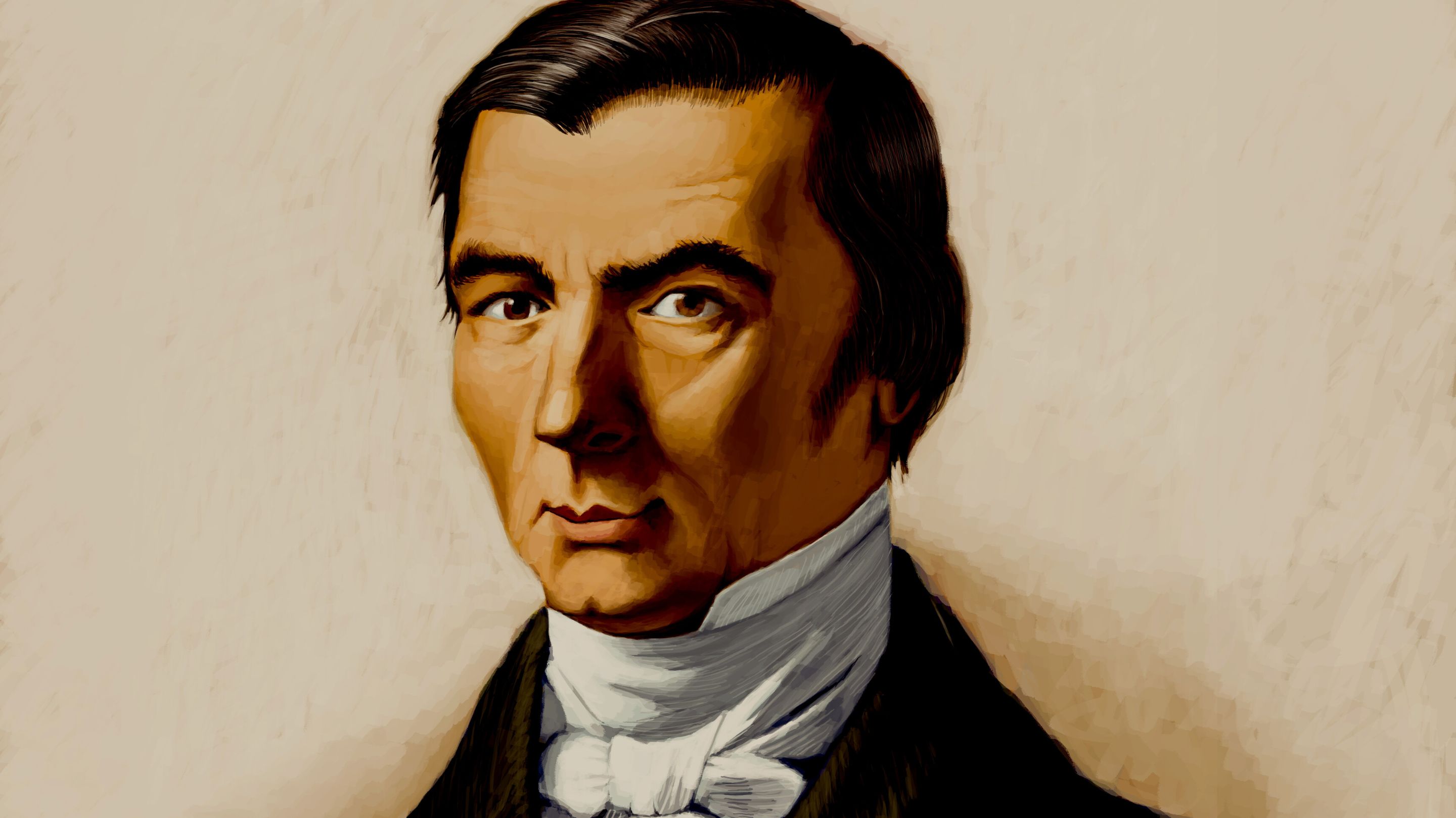

In recent years, there has been a surge in discourse surrounding the role of government, its current powers and limitations, and how it carries out justice effectively. In the United States in particular, this debate has been primarily split into two schools of thought: Large centralization and small decentralization. The former of these sees the government as an entity designed to carry out public deeds and projects to benefit society through taxpayer funding. Meanwhile, the latter believes that governments should have as limited funding and oversight as possible in order to allow individuals to determine markets, charity, and other personal projects. Though this discussion can seem particularly modern, it has been argued over for hundreds of years, with this analysis exploring the intricacies of French philosopher Frédéric Bastiat’s view on law, justice, and the government.

The French Revolution

To understand Frédéric Bastiat’s writings, it is first necessary to understand the context in which he wrote. During the late 1790s, the absolute monarchy in France was violently overthrown, thrusting the state into political turmoil which led to numerous Republics of France followed by an imperial period under Napoleon in the early 1800s. By the late 1840s, France was beginning to stabilize under a Republic once more, resulting in the all too familiar debate on what the government’s role should be in public welfare. One of the biggest issues under the old monarchy had been the plight of the average citizen while the upper class thrived. As such, there was a large call for public welfare projects to be undertaken by the new government, including education, agriculture, subsidies, etc. Additionally, to aid the lower class, many called for tax cuts and universal suffrage (primarily universal suffrage for white males - women and other minorities were discussed somewhat, though they were still mostly left out of the conversation).

It is in this context that Bastiat wrote about his fears of a socialist state in France and how the state must avoid it at all costs. Though he published many essays before his death in 1850, some of his most influential ones center around the government, the law, and how both work to uphold justice (or fail to in the case of a potential socialist France).

Law and Justice: Separate Yet Harmonious

Socialism is an economic and governmental system by which privatized ownership of industry and means of production is eliminated and put in government control. Bastiat was a staunch critic of such a system, as he believed that the government’s sole role was to enforce the law, and the law’s sole responsibility was to uphold the guaranteed liberties of each individual, namely life and property. To deprive anyone of these natural rights was a perversion of justice, so for the law to be just, it must not impede on any of these liberties. For instance, say a socialized government wishes to provide universal healthcare, a hot topic of debate even today. According to Bastiat, this program would require, if implemented from the government, funding from taxpayer dollars; however, if money is property, then the government is using its laws to strip individuals of their property, which is unjust and therefore a perversion of power. As Bastiat explains, law does not create justice - justice must create the law. Just because it is a law does not mean it upholds individual liberties, and any such laws must be redacted as they are only ways which plunder society of wealth.

It is this idea of “plundering wealth” that Bastiat puts special emphasis on, for any law which does not solely exist to protect natural rights must be exploitative in some manner and plundering the wealth of its citizenry. Governments have but two functions: give and take. Giving can never exceed the taking, and in a perfect world, the two ought to be equal; however, there is often extraordinary waste that results in much more taking than giving, resulting in a societal net negative. If the government only enacted laws which protected individual liberties and took no such taxation only beyond what was needed to enforce these basic laws, there would be no ability for corruption or societal waste to occur.

Neither Right Nor Wrong

Naturally, there are some objections to this, namely that all governmental programs would be unable to run under such a system, including public education. Bastiat’s issue is not that the public is educated, it is that the government is running it. In defense of Bastiat, the government, even under current systems, often underfunds areas of poor socioeconomic statuses, limiting the educational opportunities children from these areas have. Though the opportunity for private schooling exists, poor communities are unlikely to afford such expenses, so they are forcibly reliant on the government for a program which often underserves these demographics. The service it provides does not equate to the tax money it forcibly takes from its populace.

I further can understand Bastiat’s position in his humorous essay regarding tariffs, as he lambasts the French government in a satirical petition requesting laws to block out the sun to protect French artificial lighting industries. Obviously, such a policy is absurd and is a huge net-negative to society, and this same sentiment can be expanded to all tariffs. While they may protect industry leaders, it is the average people that suffer the most, thus stripping them of their liberties and using the law in an unjust manner. Bastiat’s position shines the brightest through stances such as this, where he critiques the corruption of the government and their catering to certain demographics at the expense of others. No government should get to play God, and Bastiat’s arguments are highly compelling when considering it in this manner.

However, a critical oversight Bastiat makes is in his assessment of what creates a societal net negative. Thus far, any time this aspect appears, he refers to property and wealth, and yet, societal value is not always something physical. Value can also include education, happiness, health, etc. Therefore, I believe his definitions can be rather limiting, and not all governmental programs should be condemned, insofar as there is no waste in their implementation. In such a system, the monetary plunder of the citizens would be remunerated in full by the government, so long as the effects are shared evenly across all members of society. Ultimately, this caveat is incredibly difficult to achieve in the modern world, but if the laws were arranged to ensure justice as Bastiat describes, I believe this alteration to his original ideas would only elevate his proposed society and generate more societal wealth in the long-term.